I recently had to re-edit some source material that lived only on a DVD. And I had to do it at home on a software-only Media Composer system. Many friends told me not to attempt this–too many settings, too many ways to screw yourself up. Better to use a good DVD player, using component or SDI outputs, and digitize via hardware: Adrenaline, Mojo or Nitris. But I didn’t have the hardware, so I persisted.

There are indeed, many, many ways to convert DVD material to Avid media, and by now, it seems like I’ve tried them all. I’ll describe the workflow I came up with below. It seems to work well and once you figure it out, it’s not all that hard to do. Quality is quite good.

The process begins with software to get the video off the DVD. On a Mac, you can use Handbrake, Cinematize, and MPEG Streamclip, among other applications. MPEG Streamclip has two advantages: it’s free, and it’ll digitize directly into Quicktime formats, including the Avid QT formats. Handbrake will only transcode into different MPEG flavors or AVI, so to get into a Media Composer you have to transcode twice. Video captured that way looked okay, and if you’ve got Handbrake I wouldn’t be afraid to use it, but I wanted to skip the extra step. I ended up with MPEG Streamclip.

Settings are critical. You want to digitize into a 480-line format. Video on DVD is 480 lines high. But standard def is usually 486 lines and those extra six lines can create problems, putting horizontal bars into your video when you output. The most common 480-line non-mpeg format is DV. But it turns out that there are several flavors of DV. If you use the standard Quicktime DV codec in an Avid, you can end up with elevated blacks. Better to use the Avid DV codec. The Avid version has another advantage. You can work at DV50, which offers twice the bandwidth and more color resolution (422) — roughly equivalent to Digibeta.

Insert your DVD and open MPEG Streamclip. Select File > Open DVD and point the application to your DVD. Pick the track you’re looking for. If necessary, open each track and play it to figure out which is which. Streamclip asks if you want to fix timecode breaks. I skipped that step.

Choose the audio track you want. If you have a two-track (dolby stereo) version on the disk you’re probably better off with that. MC doesn’t understand 5.1 and you’ll have to load the individual tracks separately. Then select File > Export to Quicktime. Here’s where the fun begins.

I set the basic import options as follows (if you have trouble seeing the screenshots, click them and they’ll enlarge in a new window). The main idea is to use the Avid DV codec at 100% quality, lower field dominance. If you’ve got 24p material on your disk you’ll want to de-telecine it, and you may need another application. I didn’t experiment with that.

Click the Options button to reveal the Avid DV Codec options. Be sure to select DV50 and RGB levels.

Then click Make Movie to begin digitizing. On a dual-core Macbook Pro this took roughly real time. When you’re done you’ll have a Quicktime-wrapped Avid DV file.

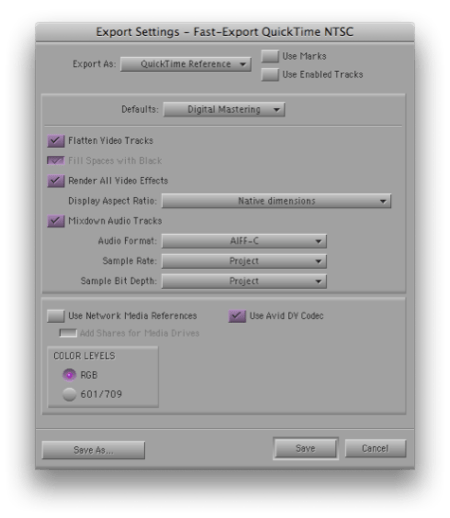

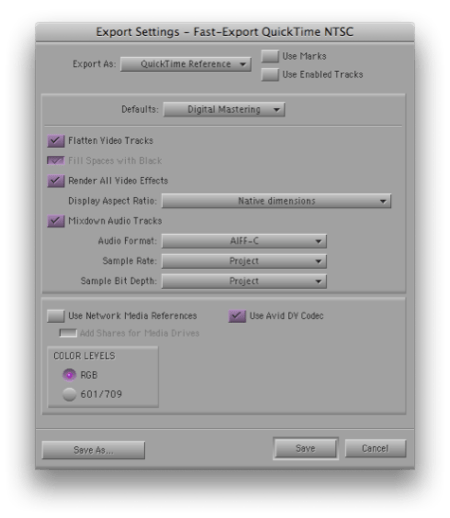

You now have to import this into the MC. The idea is to simply remove the Quicktime wrapper without altering the underlying video. To do that, you have to get the MC to do a “fast import.” Open your Import settings and set them up like this:

The critical settings are “Image sized for current format,” and “601 SD.” That’s right — you want RGB, but if you select “Computer RGB” the video will be re-encoded. The button is apparently misnamed — “601” really means “don’t muck with it.” Audio will come in first. When video starts loading make sure the progress bar says “fast import.”

When you’re done you should have a very clean-looking piece of Avid media. Mine was also very responsive, using a laptop with nothing but a Firewire 400 drive. To see the video in its full glory be sure to select the green/green quality setting at the bottom of your timeline.

Edit away, as needed.

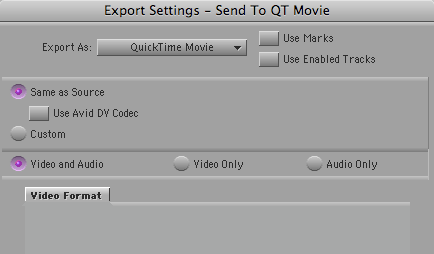

When you’re ready to output, your best and fastest option is a Quicktime Reference file. This references your Avid video media and avoids re-encoding it. You’ll want to use the Avid DV codec and set RGB levels, which is where you’ve been all along. (Of course, the reference file won’t work on another machine unless you bring your Mediafiles folder with you.)

And that’s it. Seems easy now, doesn’t it? But I must have done 25 tests over a period of a week to get all this worked out, and there are issues I didn’t fully deal with (de-telecining and using the 5.1 audio, among others). There really ought to be a better, simpler way. But without extra hardware, this approach, or something like it, looks like the best you can do right now.

Many thanks to Rainer Standke, Michael Phillips, Jeff Ruscio, Michel Rynderman and everybody on Avid-l for their help with this.

Recent Comments