In the old days, film shows turned over to sound via videotape and OMF. That meant sound got a 29.97 version of a show that was cut at 24, complete with the 3/2 telecine-style cadence inserted. It was an awkward and slow hand-over for both picture and sound.

In the old days, film shows turned over to sound via videotape and OMF. That meant sound got a 29.97 version of a show that was cut at 24, complete with the 3/2 telecine-style cadence inserted. It was an awkward and slow hand-over for both picture and sound.

Today, though most shows no longer deliver tapes to sound, many still create 29.97 Quicktimes, often for no better reason than, “it’s what we’ve always done.” But if you’re working on a 24-fps show, the easiest and simplest way to turn over is with 24-fps Quicktime.

Why are 29.97 QTs problematic? First, because creating a 29.97 QT from a 24 or 23.976 fps project doesn’t just mean introducing 3/2 — it means duplicating frames. That makes it awfully hard to cut sound effects precisely. Second, 29.97 QTs take a long time to make, wasting hours that picture assistants don’t have.

But if we turn over 24-fps Quicktimes, what settings should be used? And how should sound handle it in Pro Tools?

I’ve spent several days hashing this out with a music editor friend. I made a simple sync test: a head and tail leader with sync pops, separated by three minutes of filler and overlaid with an Avid Timecode Burn-In effect. From this I exported Quicktimes and OMFs, which my friend imported into PT. Then he added his own counters, compared them with mine and checked the pops. A pulldown sync error is about 1.5 frames per minute, so at the end of 3 minutes, if we’d screwed up, he’d be out by over four frames.

The whole thing is complicated by the fact that the Media Composer allows you to work in two kinds of 24-fps projects: “23.976p” and “24p.” The 23.976p project works like digital videotape. The 24p project works like film. (For details, see the post, Clarifying Avid Project Types. To figure out what kind of project you’re working in, go to the Project window and select the Format tab.)

Either way, you should select “Current” frame rate when you make your Quicktime. This will produce a Quicktime that is frame-for-frame identical to what you’re seeing in the Avid. (In a 23.976p project Quicktime will display a frame rate of 23.98, in a 24p project, it will display 24.)

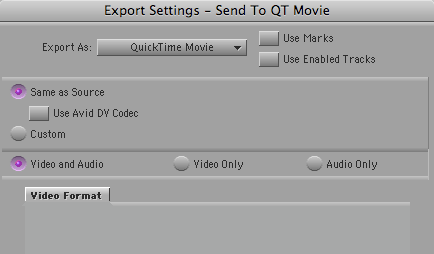

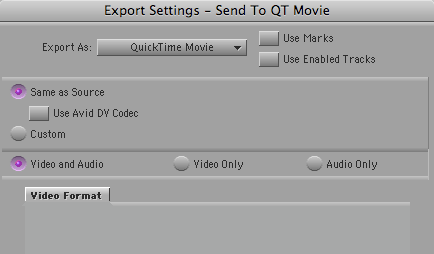

Choose any codec that you and your sound editors prefer. But consider using the Avid codec. That’ll produce the fastest QT conversion, and your sound editors will see exactly what you saw in the Media Composer. You won’t need to fool around with Quicktime export settings, either. Just select “Same as Source” in the Quicktime Export dialog and you’re all set.

To play these QTs, your sound editors will need to install the Avid codec. Many sound editors don’t have this, but it’s a trivial download and a simple install. You’ll find the codec here. (Avid really ought to make it easier to find.)

In Pro Tools, your sound or music editors will work as follows: If you are working in a 24p project, they’ll run picture and timecode at 24-fps. If you’re working in a 23.976p project they’ll run picture and TC at 23.976. Either way, they’ll play back audio at 48K (or 44.1 in the unlikely event that you’ve been working that way in MC).

That’s all there is to it. If you take the time to create a test like I did (always a good idea), your sound editors will see the tail pop from your OMF line up with the tail sync mark in your QT, and their TC counter will line up with yours. They’ll see exactly the same frames you did in the Media Composer, and your exports will be quick and relatively foolproof.

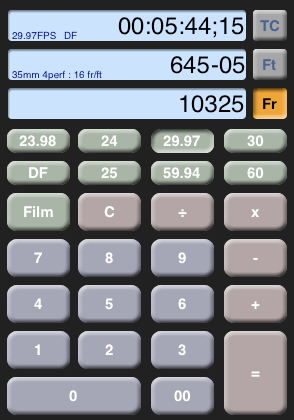

EditCalc

EditCalc

Recent Comments